Philanthropy is not a casual product; it is not a mere outcome of a

zeitgeist, or fashion of the age; its roots are deep in the soil of

Christianity; it cannot pick up a living either from Paganism, or Agnosticism,

or Secularism, or any other system cut off from the influence of the love of

Christ.

This is one of the first paragraphs

in William Garden Blaikie’s Leaders in

Modern Philanthropy published in 1884.

What follows is a barnstorming tour of all the great Christian

philanthropists from John Howard, William Wilberforce,

Elizabeth Fry, Andrew Reed, Thomas Chalmers, Thomas Guthrie, David Livingstone,

William Burns, John Patterson, Agnes Salt and many others. The claim that some make that Dr Thomas Guthrie

was some kind of lone voice in 19th century Scotland is simply not

supported by facts. Guthrie built on the

work of Sheriff Watson in Aberdeen and John Pounds in England. His work was taken up by many particularly

Lord Shaftesbury in England. He was part

of a wider movement that rediscovered evangelical theology and roused a

sleeping church to the Biblical mandate of fighting for justice and showing

mercy to the marginalised. Their work

sprang from their theology.

|

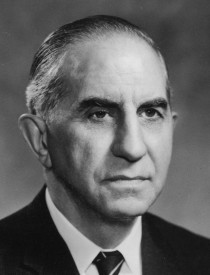

| Rev W.G. Blackie |

Despite the UK’s departure from

its Christian heritage, much of our society remains rooted in the Bible. The idea that we are all equal in the sight

of the law, the idea of education for all, the concept of compassion for the

poor are inextricably linked to a Biblical view of humanity. If you don’t think this is important look

closely at other society’s and see the radical difference. The foundational Christian belief that man is

made in the image of God has radical implications for the way we treat our

fellow man, particularly those who need special protection and care. Christianity teaches that everyone has

dignity and worth. It also teaches that

anyone can be redeemed from their fallen/sinful state. Man’s fundamental problem is not poverty,

housing or power, it is sin (Matthew 15 v 15-20). The addict, the wife beater, the thief can

all be redeemed and transformed by the grace of God. Christianity is about grace, hope and most of

all love. It is religion of redemption

and second chances.

But much more than personal

transformation, Christianity places on the believer ‘a strong dynamic impulse

to diffuse the love which had fallen so warmly on themselves’ (Blaikie). Our Saviour, ‘the friend of publicans and

sinners’ is our ultimate example. Jesus

taught repeatedly about the need to love the poor in parables such as the Good

Samaritan. His teaching in Matthew 25 on

the sheep and the goats couldn’t be clearer.

He defined true greatness: ‘the servant of all being the greatest of

all.’ Remember that Jesus was speaking

at a time when the order of the Roman empire masked a barbarous culture.

Gladiatorial sports slaughtered tens of thousands for nothing but the amusement

of the baying mob. Slavery was

commonplace and women were often used as sexual play things. Yes, there were occasional spurts of

compassion when an amphitheatre collapsed but there was no systematic relief of

the poor. It was a hierarchical society

where groups and classes were systematically oppressed and kept down. A bit like modern Britain.

It was as the New Testament

church grew and spread throughout the Roman Empire that Christianity’s counter

cultural message of love for the poor began to change societies. As Blaikie says: ‘In the course of time,

barbarous sports disappeared; slavery was abolished or greatly modified; laws

that bore hard on the weaker sex were amended; the care of the poor became one

of the great lessons of the Church.’

This is not to say that the church did not frequently go wrong. Often the methods of showing love became exaggerated

and distorted. The alms giving in the

mediaeval church became more about the abuse of power than equipping the poor

to become self-reliant. The reformation was a great return to Biblical

Christianity and while it was a time of great conflict it also saw a return to

Biblical philanthropy and care for the poor.

It encouraged education and saw the start of schools, colleges and

universities. The Bible was not only

given to the common man but he was also taught how to read it. This why William Tyndale became a hunted

terrorist. His English New Testament was

a threat because it challenged the power of a corrupt church.

So far so good. Even the most cynical atheist would surely

acknowledge that Christian philanthropy has done great good. But let’s be honest, there have been many

inspiring philanthropists who haven’t had an ounce of love for God. It is wonderful to read of philanthropists

such as Andrew Carnegie building libraries, donating ornate organs and building

palaces of peace. My family home in

Sutherland has many monuments to the generosity of Carnegie. We celebrate every effort that is made to

relieve the poor and change society for the better whether in Christs name or

not. Nobody can deny that many charities

have sprung up with little or no Christian inspiration. But history shows us that all too often the

greatest social reformers have been compelled by a zeal for God that leads to

an enduring love for his neighbour. They

inspire followers who, if not always sharing in their theology, agree with

their goals and are willing to follow their example. Often secular philanthropists (such as

Carnegie) are blessed with great fortunes and influence but it takes an

exceptional love to persevere in championing the poor without wealth or

power. It is one thing for an inspiring

political leader to rise up but unless it is underpinned with the theology of

Christian compassion, how long will it last?

|

| Dr Thomas Guthrie |

Secularism may try to keep up its spirits, it may imagine a happy

future, it may revel in a dream of a golden age. But as it builds its castle in the air, its

neighbour, Pessimism, will make short and rude work of the flimsy edifice. Say what you will, and do what you may, says

Pessimism, the ship is drifting inevitably on the rocks. Your dream that one day selfishness will be

overcome, are the phantoms of a misguided imagination; your notion that abundance

of light is all that is needed to cure the evils of society, is like the fancy

of keeping back the Atlantic with a mop.

If you really understood the problem, you would see that the moral

disorder of the world is infinitely too deep for any human remedy to remove it;

and, since we know of no other, there is nothing for us but to flounder on from

one blunder to another, and from one crime to another, till mankind works out

its own extinction; or, happy catastrophe! The globe on which we dwell is

shattered by collision with some other planet, or drawn into the furnace of the

sin.

It is the Christian gospel that

has been the great agent of change in human history. Has the church at times been corrupt? Absolutely.

Has it at times disregarded the poor and even abused them. Unfortunately, it has. But what has been the fruit of the revival of

true Christianity? It has always been

love, particularly for the poor. The

spirit of self-seeking is supplanted by the spirit of service and love. Vice is replaced by virtue. When men love God in sincerity, they will

love their neighbour, particularly the poor and the outcast. The church at its best lives by that early

‘mission statement’ in James 1 v 27 ‘Religion that is pure and undefiled before

God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their

affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.’ As Thomas Guthrie said about the kind of

Christianity that brings transformation to communities;

We want a religion that, not dressed for Sundays and walking on stilts,

descends into common and everyday life; is friendly, not selfish; courteous,

not boorish; generous, not miserly; sanctified, not sour; that loves justice

more than gain; and fears God more than man; to quote another's words - "a

religion that keeps husbands from being spiteful, or wives fretful; that keeps

mothers patient, and children pleasant; that bears heavily not only on the

'exceeding sinfulness of sin,' but on the exceeding rascality of lying and

stealing; that banishes small measures from counters, sand from sugar, and water

from milk-cans - the faith, in short, whose root is in Christ, and whose fruit

is works.

|

| William Wilberforce |